This post was originally published on Take Me Home Virginia blog and is by Connellee Armentrout. Connellee is originally from Roanoke and is a second year law student at the University of Richmond.

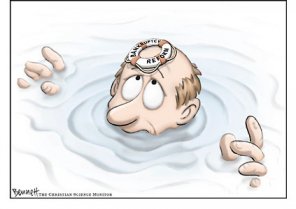

Bad bankruptcy laws have made foreclosures in Virginia, and across America, worse. The presumption is that those in bankruptcy put themselves in that position through irresponsible purchases. But often the foreclosures are the result of unexpected changes in financial position, like being laid off or having your hours/salary reduced. In the Great Recession, sound bankruptcy laws could have prevented unnecessary foreclosures. However, Virginia’s bankruptcy laws don’t allow Virginians to protect their primary residence. Also, federal bankruptcy reform allowed banks to retroactively increase interest rates on low-interest loans. In other words, even if you were smart and responsible and got a good loan, you got screwed retroactively.

In 2005, Congress passed a bankruptcy law, supported by banks and credit card companies, that made it harder for individuals in bankruptcy to alleviate credit card debt, and, in general, the law made it more difficult to file for bankruptcy. The idea was to make it harder for the individual to get rid of his credit card debt through bankruptcy. But, economists at the New York Federal Reserve have concluded in a recent paper that the law “pushed more than 200,000 people into foreclosure and exacerbated the subprime mortgage crisis.”

The problem with the law is that when bankrupt individuals are unable to alleviate their credit card debt, they default on their mortgages instead. Compounding the problem, the initial foreclosures on bankrupt individuals drove housing prices down, which pushed other homeowners underwater on their mortgage and into foreclosure as well.

Since 1993, mortgage debt has been protected in bankruptcy proceedings, such that bankruptcy courts cannot alleviate the burden, and the 2005 law tries to put a similar protection on credit card debt. But, by contrast, until the implementation of new rules in 2009, credit card companies have been able to institute “retroaction rate increases,” which allow a bank to retroactively increase the interest rate on debt already incurred at a much lower interest rate. Clearly these are unbalanced scales.

The Virginia foreclosure crisis exhibits this national trend in bankruptcy, and, in particular, Virginia bankruptcy law hits low-income filers the hardest. All bankruptcy is managed in the Federal courts pursuant to Article 1, Section 8, Clause 4 of the U.S. Constitution. State law however, especially concerning exemptions, can make bankruptcy look quite different state to state. The most common form of bankruptcy for individuals is Chapter 7, which is basically liquidation. Under Chapter 7, credit card and most other debts are paid to the extent possible with the individual’s liquidated wealth, and, in return for liquidation, the individual is assured that the debt is settled for good. However, the 2005 law made it more difficult to file Chapter 7 and to alleviate credit card debt once a person has filed, so bankrupt individuals saddled with the additional credit card debt were forced to default on their mortgages. The 2005 law went into effect October 17, 2005, and from 2006 to present there have been over 200,000 foreclosures in Virginia.

President Bush & Republican Leaders in Congress at the bankruptcy reform signing ceremony

More wealthy individuals often opt for Chapter 13 bankruptcy because there is no liquidation and the individual will likely keep all of his assets, but this option is generally not available to low-income individuals. In addition, even under Chapter 7 bankruptcy, the law favors higher income individuals by exempting group life insurance proceeds (VA Code 38.2-3549), some personal property including $5000 in heirlooms and $5000 in furniture (VA Code 34-26 & 34-28), tools of your trade (VA Code 34-26), and at least 75% of wages (VA Code 34-29).

However, it is middle-income individuals who are at the highest risk for losing their home. In Virginia there is a Homestead Exemption that protects $5000 plus $500 per dependent of personal property (VA Code 34-4). Usually, in practice this means that those with less than $5000 in equity in their home will keep their home as a exempted homestead, but those with more than $5000 in equity will have their home foreclosed and $5000 of the proceeds will be protected by the exemption. In Virginia, the home is always on the chopping block because it is not the home but rather the “homestead” that is protected. Personal property, on the other hand, such as cars, boats, or jewelry may be unconditionally protected:

(see VA Code 34-26(4)(exempting clothing), 34-26(2)(exempting heirlooms), 34-26(8)(exempting furniture), 34-28.1 (exempting a car), 34-26(1)(a)(exempting wedding and engagement rings), 34-4 (exempting homestead, which may be any personal property).

So, because of the 2005 law and Virginia’s bankruptcy laws, those filing bankruptcy now may find themselves in danger of losing their homes. Low- and middle-income filers often do not have Chapter 13 debt-restructuring options, Chapter 7 cannot wipe out mortgage debt, and the 2005 law makes it difficult or impossible to alleviate credit card debt. So, having filed bankruptcy, the individual is still on the line for his credit card and mortgage debt, and if his home has survived bankruptcy proceedings, it is likely the only asset left for creditors to go after.

The 2005 law represents a shift in thinking about the plight of bankrupt homeowners, as the law was written, at the behest of creditors, to increase the burden and blame on debtors. In addition to protecting credit card debt, the law institutes new presumptions against debtors, increases penalties, and reduces judicial discretion to balance competing interests in the pursuit of fairness.

The presumption is, as the banks argue, that those in bankruptcy put themselves in that position through irresponsible purchases. But often the foreclosures are the result of unexpected changes in financial position, like being laid off. And, long-time critic of the 2005 bankruptcy law, Elizabeth Warren, who is currently charged with setting up the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, has emphasized that consumption binges do not explain the high levels of consumer debt and financial distress seen in recent decades.