The following was originally posted on Progress Notes and was written by Dr. Chris Lillis, Fredericksburg Physician and Virginia Organizing Health Care Committee Member.

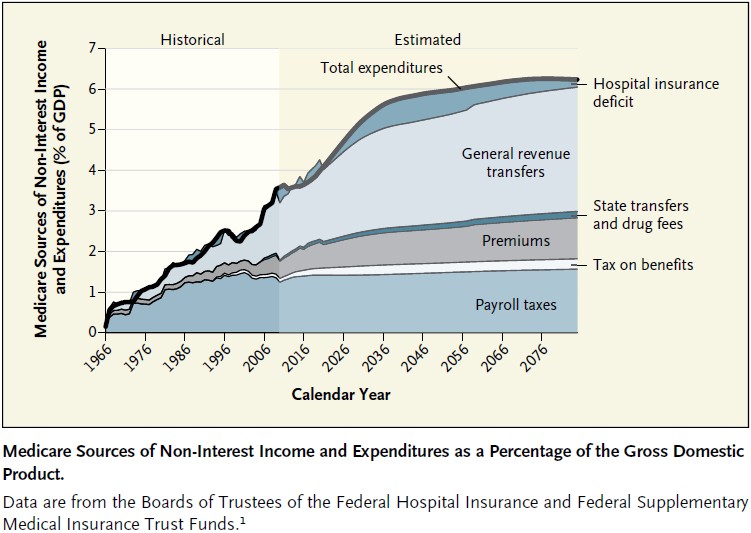

The above graph comes from a recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine, and nicely encapsulates an economic nightmare for the United States. If politicians from either party could move away from using sound bites to attract voters to their political positions, and carefully but thoroughly explain why our projected costs will result in ever growing deficits, perhaps we could begin to work towards a national solution.

Medicare – due to our aging population – is going to consume more and more of our federal budget in the years ahead. This will put tremendous pressure on our federal budget, and ignoring this reality could be our downfall.

Who is to blame?

Truthfully, when Medicare was set up 46 years ago, I doubt anyone foresaw our current predicament. Take this graph from Ricardo Alonso-Zaldivar :

“Consider an average-wage two-earner couple together earning $89,000 a year. Upon retiring in 2011, they would have paid $114,000 in Medicare payroll taxes during their careers. But they can expect to receive medical services – including prescriptions and hospital care – worth $355,000, or about three times what they put in. “

This gap, between taxes collected and spending on medical services, has been growing every year, and will continue to do so unless something changes. This is largely due to the hyper-inflation we see in health spending, alluded to earlier this week by Nilesh here on Progress Notes.

Awful ideas to fix this problem are currently being proposed in Washington, DC. Raising the age of Medicare eligibility, or changing Medicare to a voucher program are akin to using a chainsaw to remove an inflamed appendix, instead of a scalpel.

However, there are ways to keep America’s promise of Medicare benefits and the security of health insurance for seniors while making Medicare more affordable for our nation.

Dr. Robert Levine wrote this piece a few years ago, and estimates that about a trillion dollars is wasted every year in our health care system between unnecessary care, administrative waste and fraud (not all in the Medicare system, but a substantial portion). Find it hard to believe? Then you have not read enough. Physicians are part of the problem in ordering and performing unnecessary tests, procedures and surgeries, as outlined here by Dr. Rita Redberg.

Let’s take the example of placing stents for coronary heart disease (I don’t mean to single out cardiologists, but the point is clear). Placing a stent in the blocked, or more often partially blocked, coronary artery has truly only one benefit – to alleviate present chest pain caused by that blockage. Placing coronary stents does not extend the life of the recipient, yet stent usage continues to grow.

Some calculations (rough, back of the envelope) :

– National Medicare reimbursement ranges from $10,000-$16,000 for coronary stenting

– Roughly 8000 stents placed per month in Medicare beneficiaries = 96,000 stents per year

– Up to 50% may be outside of clinical guidelines, making them unnecessary

– $13,000 per average stent x 96,000 stents per year = $1,248,000,000 ($1.3 billion)

– Half unnecessary = $650 million per year wasted

– In Washington D.C. terms, $6.5 billion in unnecessary spending per 10 year budget window

The example of coronary stenting is an easy one for several reasons. 1) It is very expensive, and does not seem to help improve health in stable heart disease patients 2) The average member of the public gets pretty angry if they know that a physician undertook a risky procedure for personal financial gain rather than the benefit of the patient, and 3) we are starting to see prosecutions of the most egregious cases of fraud and abuse.

I am not alone in proposing an alternative to gutting benefits or keeping our collective heads in the sand. My favorite health economist Austin Frakt also knows we can “bend the cost curve” in relatively painless ways if we all admit where we are making mistakes and tweak the program. His ideas are substantial:

1. Competitive bidding, also known as competitive pricing. This idea really puts the market to work to buy Medicare benefits for the lowest possible price on a market-by-market basis. Participants can be public and private entities. It piggybacks on the existing, hybrid structure of Medicare (FFS Medicare + Medicare Advantage) and makes all participating plans compete directly in a way they never have. Scholars have estimated the savings to be 8% of Medicare spending. I’ve written a lot about this elsewhere. Perhaps this post is the best place to start.

2. Competitive bidding can be put to work for durable medical equipment too. See the work of Peter Crampton.

3. Part D formulary design and drug pricing. Did you know the VA buys drugs for 40% less than Medicare? True! That alone suggests Medicare could spend a lot less on drugs. There are many possible Part D reforms that would lower program spending. Kevin Outterson wrote about some. For more about what it would take and mean to make Medicare’s drug benefit more like the VA’s see my post, which links to my paper with Steve Pizer and Roger Feldman.

4. Reference pricing. This idea came to me via David Leonhardt and Peter Orszag (smart guys, by the way; you should talk to them). The basic idea is that Medicare should only spend an amount on therapy for a condition equal to the lowest cost, effective one (that’s the “reference price”). If individuals want more costly therapies that are no more effective, they should pay the difference out of pocket. There’s more to this. See this prior post and related links therein.

5. There are lots of things Medicare shouldn’t even be paying for at all because they don’t work. See Rita Redberg’s NY Times op-ed on this.

6. Support comparative effectiveness research so we can learn more about which therapies are most effective. There is too much we don’t know and it is costing us.

7. Let ACOs be tested. We don’t know if they’ll work, but they’re worth a try.

8. Support the IPAB. Isn’t it obvious by now that Congress itself can’t control Medicare costs?

9. Consider all-payer rate setting. More on that here. Perhaps this post is a good starting point.

Opponents of health reform and its potential financial savings, who frequently are hypocritically in favor of deficit and debt reduction, will say that none of this will work. I challenge you to watch this video and ignore the naysayers. We can solve these problems, if only we target the right problems.