By Elizabeth Simpson

By Elizabeth Simpson

The Virginian-Pilot

© December 15, 2014

The army of counselors who help people sign up online for insurance in the Affordable Care Act marketplace this open enrollment period face a range of reaction.

The sessions usually end in gratitude – and sometimes insurance for someone who has been going without a safety net. But occasionally there’s frustration, even anger, from people who find the premiums and deductibles in the federal marketplace too much for their pocketbook.

Many of the disappointed fall into the so-called “coverage gap,” those whose incomes are below the lower limit for subsidies on the marketplace but above the Medicaid eligibility line.

Virginia decided not to expand Medicaid, the state-federal insurance for low-income and disabled people – which would have covered up to 400,000 Virginians – and it already had one of the toughest eligibility standards in the country, sixth-most stringent by one report.

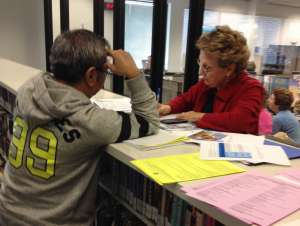

“In some cases, they would have to pay 25 to 50 percent of their salary, and that is not affordable,” said Virginia Beach Health Director Heidi Kulberg, who was overseeing a recent ACA sign-up session at the city’s library. “We try to take the time to explain, in a nonpartisan way, that they would have been covered, but the Supreme Court ruling on Medicaid expansion came out, and the state decided to opt out. People look at us like, ‘Why won’t you help me? Obamacare is no good because it’s not helping me.’ ”

It’s a familiar sentiment in the 23 states that opted not to expand Medicaid after the 2012 U.S. Supreme Court ruling saying it was not mandatory. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 171,000 Virginians are within a group of 3.8 million Americans who fall into that gap between subsidies and Medicaid coverage – most are clustered in Southern states, according to Laura Snyder, senior policy analyst at Kaiser.

In Virginia, 70 percent of them have someone in the family who works. Forty-four percent are women. Nearly 80 percent don’t have dependent children. Across the country, about half are women, and half are ages 35 to 64.

Many join the ranks of uninsured people like Myra Simms, who didn’t even bother to go online or to a counseling center to check out the prices.

Rather, she went to the Beach Health Clinic on Holland Road for free care. She’s 55, and her children are grown. She used to work as a housekeeper in hotels and retirement facilities. When she worked full time and was offered health insurance, she turned it down.

“When they take $200 from your paycheck, that’s not good,” she said.

She suffered a heart attack four years ago and had an operation to have a heart stent implanted in October. She takes 15 pills a day and receives most of the medicine from the clinic, which provides services to the uninsured for free.

She hasn’t checked to see how much plans cost on the ACA marketplace because her employment is regularly interrupted by illness, and any premium would be too much.

“Every time I’ve had a problem I come to the clinic,” Simms said. “I worry about the day they might not be here.”

The lack of expansion is just one reason why some free clinic directors say it’s business as usual in terms of caseloads. Donations, though, are tougher to come by because people think the ACA has solved the problem of the uninsured.

Susan Hellstrom, executive director at Beach Health Clinic, said pharmaceutical companies aren’t donating as many medications, and grants are harder to obtain.

Some free clinics in Virginia planned to reinvent themselves by accepting Medicaid patients if Virginia expanded, but they held off because the commonwealth opted not to.

One of them, Chesapeake Care, is now in wait-and-see mode and scrambling for revenue. In 2012, it instituted a $20 dental visit payment, followed by an additional $10 per visit in 2013. In October, the clinic became a Medicaid dental provider to increase revenue through that funding stream.

Meanwhile, Cathy Revell said their caseload is as large as it has ever been: “We’re still a safety net provider. That has not changed.”

She said Chesapeake Regional Medical Center, one of the clinic’s major community partners, is limited in its capacity to help. Hospital officials expect $4 million in ACA-related losses in 2015; Medicaid expansion would have brought in $5.6 million next year.

“It makes planning impossible,” Revell said. “We’re holding our breath to see what will happen.”

For hospitals, the Medicaid expansion was expected to help reduce the amount of uncompensated care. Rob Broermann, chief financial officer at Sentara, said that system estimated it would have received $25 million to $30 million a year had Medicaid expanded.

However, uncompensated care rose by 6 percent for Sentara hospitals in 2014. That’s a smaller increase than the previous year, when it was 19 percent.

Federal funding known as “disproportionate share hospital” payments help defray the costs of uncompensated care, but ACA is designed to reduce those payments over time as more people become insured.

While the full impact of that shift is yet to come, other factors have hurt hospital finances, some relating to ACA and some not: readmission reductions, changes to Tricare insurance that siphoned off some care from Sentara hospitals, a medical device tax, the struggling economy.

Officials at Bon Secours Hampton Roads say that for 2015 and 2016, they expect to lose $41 million in ACA- and Medicare-related cost containment efforts for the three local hospitals. Medicaid expansion would have brought in about $45 million during that time.

Dr. Toni Miles, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Georgia and author of “Health Care Reform and Disparities: History, Hype, Hope,” believes Southern states will face a perfect storm in coming years because they have the highest number of people in the coverage gap.

Those states will see cutbacks in Medicare dollars at the same time and be hit with reductions to disproportionate share hospital payments.

While Miles appreciates work being done by free clinics, the facilities can sometimes be used by opponents of Medicaid expansion as a Band-Aid answer to a problem that’s too big for the fraying network.

“Free clinics are not that widespread, and they don’t serve that many people,” she said. “I’m not saying ACA is perfect, but the gap needs to be fixed.”

Insurance counselors, meanwhile, are doing a brisk business educating people about 2015 ACA offerings in city libraries, community health clinics, churches and other community centers throughout Hampton Roads.

While many Virginians still find the price tag too steep, others are appreciative – such as people with pre-existing conditions whose insurance rates were so high they couldn’t afford them.

Like Phil Grochmal. The 62-year-old single Chesapeake man suffered a heart attack in 2008 when he was living in California. At the time, he was fully insured through his job with a finance service. His insurance paid all but $1,000 of his $50,000 medical bill.

When he moved to Virginia in 2010, his part-time job didn’t offer insurance. Buying it through COBRA would have cost $600 a month, and a pre-existing condition made an individual plan cost-prohibitive.

He went 40 months without insurance, nervous that something would happen or his heart condition would flare up. Last year, he signed up for an ACA plan, qualifying for a subsidy that kept his premium at $107 a month. Even with a $3,750 deductible, he was happy.

“It’s a godsend,” he said. “You can live a normal life and not have anxiety about not having insurance.”

Grochmal was one of 216,000 Virginians who were enrolled in ACA plans this year, part of 7 million nationally. About 80 percent of those enrolled in Virginia qualified for financial assistance.

According to the Virginia Consumer Voices for Healthcare, 300,000 were found eligible for financial assistance on the marketplace last year but walked away, many because they still couldn’t afford the premiums and deductibles. Those are people that enrollment counselors are hoping will say yes this year, and who may be nudged to by penalties for the noninsured that will be levied for the first time during 2015 tax time.

The open enrollment period for 2015 that began last month has had 1.4 million takers nationally. State numbers are not yet available. Enrollment is open until Feb. 15, but if people want coverage to begin on Jan. 1, they need to sign up by the end of today.

Meanwhile, the discussion of Medicaid expansion is stalled in a political standoff in the General Assembly. Virginia’s legislative watchdog agency, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, declined last week to do a comprehensive study of Medicaid and instead asked both houses of the General Assembly to define specific areas of study, which officials have pledged to do.

Bill Hazel, the state secretary of health and human resources, said earlier this month that expanding Medicaid beginning July 1 would bring in more than $230 million in federal money, alleviating 71 percent of the state’s $322 million budget gap.

Gov. Terry McAuliffe is still committed to expanding Medicaid in Virginia, and The Associated Press reported over the weekend that he’s including funding for it in a budget proposal he’s releasing later this week. But foes of the idea vow to fight it, worried about costs to the state when federal funding tapers off. Christina Nuckols, the governor’s deputy communications director, said the administration is wrestling with budget issues, and that the two issues are intricately tied.

As for Grochmal, he’s not applying for an ACA insurance plan for 2015. He recently got a full-time job, with insurance. He says he’s a cheerleader for health insurance – through the marketplace or otherwise – and hopes to never suffer through another 40 months without it.

“It gets the monkey off your back,” he said.