Published by Social Policy: Organizing for Social and Economic Justice

Credibility counts

Brian Johns is the organizing director of Virginia Organizing. Recently his wife Paige answered their phone, and Brian heard her voice assume the tone she uses for telemarketers. After asking a few questions, she said, “I want to learn more about that first,” and hung up. Obviously frustrated, Paige said the caller from a national organization rushed through a script, couldn’t answer questions, and asked her to make a call in support of a Senator whose name she didn’t recognize.

Ellen Ryan is the former lead organizer for Virginia Organizing, and now lives in Maine. She received a call from a statewide organization she has supported financially and in other ways for the last seven years. The phone canvasser asked her to call her state legislator about Medicaid, but gave her contact information for someone who is not her legislator. When questioned, the canvasser insisted that Ellen was misinformed about who her legislator is, but it was the canvasser who had inaccurate information.

Funders want deliverables

Receiving calls to take action on issues is common in many states. Funders have invested heavily in national policy campaigns for the last few years, and pre-scripted calls, mailings, and media events are required “deliverables” that funders, usually through intermediary campaign organizations, contract with various groups to produce. Quality and accuracy suffer when groups scramble to produce results without building an organizational base in communities. Active and potential supporters get completely turned off when campaign operatives can’t have reasonable conversations about issues and elected officials.

There’s a better way to allocate funds to cultivate engaged citizens and produce progressive change. For example, imagine getting a call from a member of a group who lives in your community and is trained in phone banking and one-to-one conversations. Instead of rushing through a script, the caller asks you to talk about the issues you care about. Imagine tossing ideas around and asking detailed questions, finding out by chance that you both have children in the same school. Imagine that the caller tells you she’s in a room with other people from across the community making calls together about issues people are interested in. Maybe the call ends with an invitation to a local meeting in a public place, where community members get better acquainted, make plans to do something about the issues they care about, and hear about the work going on in other local groups across the region on local, state, and national issues.

You might say no, but you wouldn’t feel insulted. Imagine that you notice an announcement about the same meeting a few days later in your church bulletin with names of contact people you recognize, and the same person calls again to let you know what happened at the meeting and asks what you think. You may even see her the next day in the school parking lot where you both pick up your children after work, and walk over to introduce yourself in person. This is a much better way to do a phone bank than misdirecting scripted calls from nowhere into the wrong districts. Building powerful organizations requires treating people with genuine interest and respect. It’s how effective community organizations get started and grow. Campaigns need trained, experienced leaders in local communities, and community organizations need the time and money it takes to cultivate community leaders.

However, many state and local groups accept contracts to produce deliverables for campaigns because it’s the only way they know of to get enough money to keep the lights on. Producing campaign deliverables, not organizing communities and developing leaders, has become the primary reason some groups exist, and no real leadership base in communities gets built. Developing community leaders to carry out organizing work requires time, money, and organizers who cultivate community action consistently over long periods of time.

Funders and national campaigns need to support and expand sustainable community organizing and creative strategies that build power among people traditionally left out of decision-making, especially in states where few powerful membership organizations exist. By focusing on campaign deliverables – five hundred completed telephone calls, ten rallies, and thirty meetings with your Senator – without supporting strategic leadership development and long-term community organizing, the movement for social and economic justice is missing out on an opportunity to unleash thousands of community leaders to forge sustainable power for change – not just for the campaign of the moment, but also for the many to come. There are alternatives to campaigns-in- a-box style mobilizations that produce outcomes more valuable and durable than incomprehensible phone calls and watered-down policy votes won and lost by a nose. Community organizing is one of those alternatives, and we’ll use Virginia Organizing as an example of what it takes to develop leaders who can work effectively on any issue that comes up, without waiting for a campaign staffer to tell them what to do.

Funders want deliverables

Receiving calls to take action on issues is common in many states. Funders have invested heavily in national policy campaigns for the last few years, and pre-scripted calls, mailings, and media events are required “deliverables” that funders, usually through intermediary campaign organizations, contract with various groups to produce. Quality and accuracy suffer when groups scramble to produce results without building an organizational base in communities. Active and potential supporters get completely turned off when campaign operatives can’t have reasonable conversations about issues and elected officials.

There’s a better way to allocate funds to cultivate engaged citizens and produce progressive change. For example, imagine getting a call from a member of a group who lives in your community and is trained in phone banking and one-to-one conversations. Instead of rushing through a script, the caller asks you to talk about the issues you care about. Imagine tossing ideas around and asking detailed questions, finding out by chance that you both have children in the same school. Imagine that the caller tells you she’s in a room with other people from across the community making calls together about issues people are interested in. Maybe the call ends with an invitation to a local meeting in a public place, where community members get better acquainted, make plans to do something about the issues they care about, and hear about the work going on in other local groups across the region on local, state, and national issues.

You might say no, but you wouldn’t feel insulted. Imagine that you notice an announcement about the same meeting a few days later in your church bulletin with names of contact people you recognize, and the same person calls again to let you know what happened at the meeting and asks what you think. You may even see her the next day in the school parking lot where you both pick up your children after work, and walk over to introduce yourself in person. This is a much better way to do a phone bank than misdirecting scripted calls from nowhere into the wrong districts. Building powerful organizations requires treating people with genuine interest and respect. It’s how effective community organizations get started and grow. Campaigns need trained, experienced leaders in local communities, and community organizations need the time and money it takes to cultivate community leaders.

However, many state and local groups accept contracts to produce deliverables for campaigns because it’s the only way they know of to get enough money to keep the lights on. Producing campaign deliverables, not organizing communities and developing leaders, has become the primary reason some groups exist, and no real leadership base in communities gets built. Developing community leaders to carry out organizing work requires time, money, and organizers who cultivate community action consistently over long periods of time.

Funders and national campaigns need to support and expand sustainable community organizing and creative strategies that build power among people traditionally left out of decision-making, especially in states where few powerful membership organizations exist. By focusing on campaign deliverables – five hundred completed telephone calls, ten rallies, and thirty meetings with your Senator – without supporting strategic leadership development and long-term community organizing, the movement for social and economic justice is missing out on an opportunity to unleash thousands of community leaders to forge sustainable power for change – not just for the campaign of the moment, but also for the many to come. There are alternatives to campaigns-in- a-box style mobilizations that produce outcomes more valuable and durable than incomprehensible phone calls and watered-down policy votes won and lost by a nose. Community organizing is one of those alternatives, and we’ll use Virginia Organizing as an example of what it takes to develop leaders who can work effectively on any issue that comes up, without waiting for a campaign staffer to tell them what to do.

The movement away from grants to contracts

When Virginia Organizing formed in 1995, the common practice of private and public grant-making foundations was to accept proposals from non-profit organizations that operated in the foundations’ fields of interest. Community-organizing groups represent just a tiny slice of the non-profit organizations funded by foundations, and competition for grants from the few foundations that fund community organizing has always been stiff.

However, it was possible for people in community organizations with access to public libraries to research foundations that made grants to community organizing groups. Any organization could contact a foundation and make a proposal for funding. Successful organizations did their homework to make sure, among other things, that their organizations fit the foundations’ fields of interest before applying. The local boards of directors and leadership committees of the best community organizations sat down about once a year to make solid plans. Those plans hammered out by local leaders based on the needs they saw in their own communities became written proposals for funding from the community organizations to the foundations. Leaders could answer funders’ questions about their plans during site visits or telephone conversations. If a foundation made a decision to fund an organization, the money was used to support the plan submitted. At a minimum, the foundation required written progress and financial reports during the grant period. Some also required attendance at various conferences and meetings convened by the foundation.

General-support funding for community organizing still exists, although it is increasingly scarce. The Catholic Campaign for Human Development was, and still is, the largest general-support funder of community organizing in low-income communities nation-wide. But the revenue from its national collection for distribution as grants across the United States and U.S. territories has been reduced from $12 million in 1991 to $9 million in 2013, with $1.5 million earmarked for a single-issue initiative. The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation provided about $5.3 million for community organizing nationally through its Pathways Out of Poverty – Building Strong Communities Program in 2012, but eliminated community organizing as an area of interest in 2013.

Although few national foundations make general support grants for community organizing, some make project support grants, which fund a specific project proposed by the organization within its organizing plan, but not the plan as a whole. Rather than provide general support for an organization’s plan to work on membership recruitment, leadership development, affordable housing, job creation, school reform, water quality, and fundraising events to support the entire organization, for example, one foundation might support only affordable housing work, another only school reform, another only water quality. So an organization needs to chop its annual plan into many project proposals to many potential project funders. Like general support, getting project support for community organizing groups is highly competitive.

If lucky, the organization receives many small grants to work on various issues, but must also generate multiple reports in various required formats and send representatives to meetings convened by many funders. Early in its history, Virginia Organizing’s executive director negotiated agreements with almost all of its funders to provide a complete report of all its chapter development, leadership development, education, training, issue, fundraising, and financial activities in one standard format rather than individual reports to each funder. This not only streamlined the paperwork and saved administrative costs. It provided the organization with a complete record of its work, outcomes, and progress in meeting its own goals. The same coherent report could be used in several other ways, including background reading for evaluation meetings by leadership, posting portions on the website for public information, orientation reading for new members and staff, and public relations in cultivating potential donors.

But access to general support and project support for grant proposals from community organizations to foundations has become increasingly scarce. Meanwhile contracts initiated by foundations, usually through national campaign organizations, to community organizing groups are on the rise.

The funding shift has costs

The Virginia Organizing board, staff, and leaders, some of whom have been active since the first organizing committee meeting in 1995, meet regularly and set long-term goals to build chapters, develop leaders, and raise enough money to organize in ways they think make the most sense in Virginia. Local leaders and organizers then organize, strategize, and work on campaigns to meet those goals. Many national groups and campaigns, on the other hand, have focused on states with large labor unions or progressive networks of advocacy groups that include fewer people, mostly paid staff, in carrying out the planning and work of their organizations. Their emphasis is on winning the campaigns rather than using them as tools to develop new leaders and cultivate relationships with strong coalition partners.

As a result, the national campaigns don’t make grants to organizations to carry out organizing work in ways that make the most sense to the organizations in various states. Instead, the campaigns sign contracts with organizations to produce specific things in their states, like phone calls, media events, and meetings with members of Congress. These deliverables are quantifiable activities the organization must produce in order to receive payment under the terms of the contract.

Strategy, tactics, schedules, and talking points for national campaigns are set by national campaign staff, usually without strategy meetings to include the unpaid leadership or staff of community organizations with which they contract. This is a top-down approach to social change that is difficult to manage in organizations like Virginia Organizing that are built from the bottom up. More importantly, the national campaigns don’t benefit from the rich diversity of experience, strategies, and tactics developed by local groups throughout the country. Creativity gets lost in the assembly-line process of meeting production quotas, and active supporters accustomed to having a say in dynamic group decision-making and action get bored, or worse insulted, when presented with a script sent down from people they don’t know in Washington, D.C.

Something even deeper gets lost when small groups of funders decide what should be done without listening to the ideas of people on the ground about what needs to be done or selecting the best ideas from a vast array of competitive proposals. Community groups forget or never learn how to make their own plans as they busily follow game plans written from afar. Some groups formed after 2008 or so have no memory of making their own organizing plans, collecting membership dues, dreaming up creative grassroots fundraising events, and applying to funders to help carry out the work they cut out for themselves. The majority of foundations no longer accept unsolicited proposals, and it becomes more difficult each day to find and start conversations with the ones who do. This leaves community organizing groups with fewer alternatives to the assembly-line production of national campaign contracts.

The shift to funding organizing through national intermediary campaigns has happened quietly without press conferences. But it has had major impacts on how organizing is done in Virginia and across the country. Even though the President worked as a community organizer, and more people than ever before are aware of something called community organizing, the current funding structure is doing more harm than good to the progressive movement’s ability to organize long-term powerful organizations.

The country seemed to be on the edge of a transformational moment as people turned to the Occupy movement and fought state legislative attempts to destroy unions. However, national campaigns and funders have responded to this potential by pushing federal legislative objectives rather than pouring water on the roots of local organizations that engage people in becoming leaders who can work with others to devise and move strategies for change. While many groups like Virginia Organizing stay faithful to community organizing, the shift in the way organizing is funded weakens the movement, confusing community organizing with flash-in-the-pan policy campaigns that leave no organizational leadership or infrastructure behind to maintain pressure for better policy outcomes and move on to other issues in the future.

Deliverables, reports, and conference calls

In general, having concrete ways to assess an organization’s performance — and deliverables are just one way — is a good thing. However, most national campaigns and networks paying community organizations as contract labor define the deliverables in Washington D.C., usually with little input from the groups actually doing the work. Labor unions also provide some funding for campaign organizing, sometimes sending dozens of organizers into an area for a three to six month campaign blitz that leaves little to build on when they leave. Hiring a few organizers to stay in the same place for a number of years would accomplish more, cost less, and cover the same amount of territory.

Instead of funding multi-issue organizing or infrastructure, national campaigns fund specific issue work with a game plan written by the funders or their designated managers. Not only does this tend to create situations where organizers in some multi-issue organizations must be assigned to one issue — and thus not available for local leadership development and long term organizing — but it also creates a new middle level of work doing frequent, often daily, reports and attending conference calls every week solely about a national campaign. Those calls, meetings, and reports take up time that could be devoted to organizing rather than just reporting on and talking about it. Tying up people and resources in bureaucratic layers rather than unleashing them to get the work done is simply bad management.

Using organizers as contract labor who execute playbook tactics rather than letting them listen to members and bring them together in groups to plan and carry out strategies for change truncates organizers’ development. It threatens to reduce a complex craft to salesmanship and bean counting. Seasoned community organizers are best used to build organizations and develop leaders, but new organizers can’t learn those skills if the role of an organizer is defined as following instructions from outside the community to mobilize individuals rather than building group power within the community.

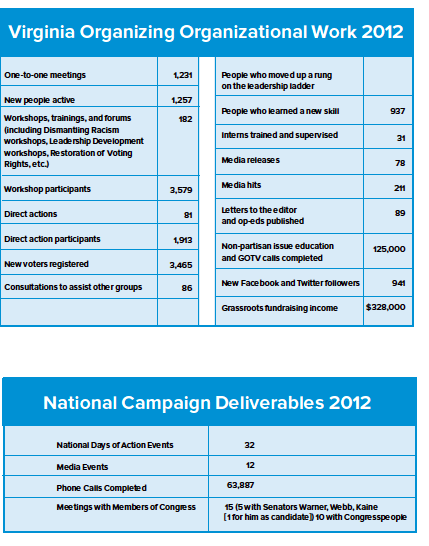

To make sure Virginia Organizing continues to build its power, it uses its own measures of progress together with the lists of campaign deliverables. The table below illustrates how Virginia Organizing manages to build the organization and produce contract deliverables at the same time. For the most part, general support and grassroots fundraising, not campaign contracts, fund organizational development, as the table illustrates:

In the past, numerous national legislative campaigns have succeeded without cookie-cutter strategy, command, and control from the top. The Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, Community Reinvestment Act, Farm Credit Reform Act, Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Civil Rights Act, and Voting Rights Act resulted from creative, coordinated activity by people directly affected by the issues based in local organizations all over the country that put pressure on decision-makers and won over the minds and hearts of ordinary citizens.

No one would measure the effectiveness of Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, Gardenia White, Rosa Parks, Septima Clark, and other on-the-ground organizers of the civil rights movement on the basis of the number of phone calls they completed, headlines they generated, and meetings they arranged with their members of Congress. These women were strategists, not color-by-number contractors. Passing legislation is a means to an end, not the end itself, as the undone work of the movements that pushed for passage of the legislation above attests. The work for justice is continuous, and it takes people who can think and work like organizers and leaders, not just check off deliverables, to get things done.

Everything is a crisis

Virginia Organizing has worked on at least five campaigns in the past five years that national groups have characterized as “the most important campaign of our lifetimes.” With this as an unexamined excuse, organizations are asked to meet with elected officials, host big rallies, and get people to make phone calls based on the assumption that the scripted campaign is the most important and only thing they should be doing. This constant crisis mode is deadly to grassroots-organization building. Treating a campaign tactic as extremely urgent makes sense if it’s true and part of an ongoing effort that includes work to identify and train leaders and build an organization. However, if an organization has resources only to work on “urgent” campaign deliverables, there is no time, energy, or money left for building groups and developing leaders. Eventually it comes across as disingenuous to both members and elected officials if every issue an organization brings to them is a full-blown crisis.

We risk missing the forest for the trees

The current national legislative focus does not allow groups to spend much time creating conditions for another large-scale movement. Although national groups and networks see the potential energy for a movement, instead of creating infrastructure at the base by funding leadership development, local organizing, grassroots education work, and meetings of local organizers and leaders to shape coordinated strategy, they focus on what they can win immediately on federal legislation. Groups are asked to do the same types of work – phone calls, town hall meetings, meeting with legislators, and large rallies – on whatever the “most important issue of our lifetimes” happens to be this month. Grassroots groups are constantly asked to contact their senators and congresspeople on that issue but aren’t expected also to engage in a long-term strategy to build the power of their organizations.

A supervisor from one national campaign actually said, “If there are no headlines from an event, that event did not happen.” So thirty local meetings to train 200 local leaders to make good media presentations are thirty events that didn’t happen. One hundred face-to-face conversations with Latino immigrants to get to know them and what issues they think are important are 100 events that didn’t happen. A dozen house meetings to introduce people to one another and talk about working on an issue together didn’t happen. If organizations and campaigns are judged solely on deliverables like the headlines they generate, calls they complete, and contacts they make with legislators, they will never build organizations that achieve long-term outcomes, like federal legislation with teeth, because leadership development, constant pressure, and winning hearts and minds do not often generate headlines. Neither did the strategy sessions, non-violence training, and relationship building with allies that went into the Freedom Rides, lunch counter sit-ins, and Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Legislators know the difference between staged press conferences and deeply engaged constituents with solid allies.

Many groups with small staffs think they have no choice but to ignore the forest and focus on the trees right in front of them in order to pay the bills. Healthcare reform and immigration reform are good examples of national campaigns community groups can help to organize and win. Virginia Organizing’s experience is that the way to win, and stand back up to fight again when you lose, is through decades of local, statewide, and national on-the-ground organizing coordinated by people actually doing the work. A monoculture of legislative campaigns organized around one-size-fits-all tactics determined from a distance diverts resources from the organizational development work it takes to be effective over the long haul.

Current national campaigns leave out rural communities

Another side effect of the shift to national campaigns has been that national groups and networks tend to discount the power of rural communities — or whole regions like the South — because it is much harder to organize large events in those places, and many federal elected champions on progressive issues represent more densely populated blue areas. It’s just easier to mobilize people in liberal urban centers.

Ellen screened the film Fundi: the Ella Baker Story for a group of new young organizers in Boston a couple years ago. In the discussion that followed, they were confused that the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) chose Mississippi as a place to work. They assumed the organization would have picked an easier place to organize for civil rights.

Maybe the leaders in SNCC, many of them college students with roots in the South, thought that making a difference in one of the worst places was a decent thing to do. Maybe they thought they could build on the hard work already done by other organizers in Mississippi, or that the people most directly affected by racism were the perfect people to lead in the demand for change and decide what those changes should be. Maybe they realized that if people in Mississippi could stand up to change their own situation, their courage would inspire others to act. Or that if they could win in Mississippi, they could win everywhere.

Policy advocates in Washington, DC didn’t script Mississippi Summer. Countless local, state, and national organizations helped rather than told SNCC what to do, while others disagreed and tried unsuccessfully to control the strategy. Without a script, professionally crafted message, schedule of press conferences, or a single smart phone, people on the ground in Mississippi changed the minds and hearts of enough of the nation to change forever racial politics in the South and the entire country. It took years. It took more than Mississippi, including every battle that came before and after it. And it worked.

At Virginia Organizing, people matter, asking people what they want to change and how they want to go about it with other people matter. Asking them what they already know and what they need to know matters. Winning matters, but dusting ourselves off after we lose and trying to win again matter just as much. We have to face one another and ourselves the next day, win or lose. The distribution of political power in Virginia means that everyone matters, and bringing together urban, rural, small town, and suburban people into organizations and alliances that work together over time is the way Virginia Organizing and other multi-issue organizations in rural states exercise power and win. Campaigns that try to work “efficiently” in rural districts or states when they want to get the attention of a legislator by generating calls from nowhere like the one Brian’s wife Paige or Ellen received not only squander the resources they have, they turn people off, sometimes the people they need most to do the work to get things done.

Even if you’re the smartest person in the room, you can learn something

Many of the national campaigns and networks have very smart organizers on staff that have done on-the-ground organizing. So it’s puzzling that most of the campaign strategies and tactics they develop don’t feed the needs of deep community organizing. The tactics are bland assembly-line deliverables, and the end game is always generating media coverage. Often the tactics don’t work well in all locations, or the locations don’t make sense for the events. This is a big country with many creative styles and traditions of organizing.

Virginia Organizing has been asked numerous times to produce large rallies or turn out dozens of people for events that don’t make sense to local leaders and members. Organizers need to work with people to design rallies and events that do make sense. For example, asking those unpaid leaders and members to help craft the events they go to usually produces results that meet deliverable requirements and makes sense to people. More importantly, it leaves room for people directly affected by the issue to exercise their own power and use it to take responsibility for achieving the best outcome possible. It stimulates ownership and commitment to the campaign.

For example, one national campaign deliverable for Virginia Organizing was to produce a media event on a specific bridge in a key Congressional district to draw attention to the need for infrastructure repairs. National campaign staff didn’t know that bridge was already undergoing major repairs. Although the event might have taken place on the bridge and counted as a deliverable, members wanted an event that clearly illustrated infrastructure needs, so they chose another location that made sense.

Micro-managing cookie-cutter deliverables leaves little room for national staff to listen to people in the local organizations and ask for their ideas. Such a process takes longer but builds stronger organizations and outcomes. National campaigns and funders need to focus more on the power and value of community organizing and give organizers and leaders room to practice it, thus informing the campaign as much as being informed by it. This takes mutual trust, and it grows from working together with people rather than designing deliverables from a distance. Funders and donors who seek progress on national policy reform need to incorporate direct support for community organizing in their mix of interest areas to support the basic structures that make effective national campaigns possible.

Leadership development is never a deliverable

The biggest problem with the current situation is that leadership development is never listed as a deliverable on contracts for organizations in national campaigns. The reason may be that it takes time, which isn’t available when everything is urgent for the most important campaign of our lifetimes, so leadership development is a luxury national campaigns can’t afford. Or it may be that the campaigns are willing to pay only for deliverables, not the work it takes to build the base of people capable of delivering them. This is the major flaw in funding organizing focused solely on national campaign objectives. Without general support to develop organizations and leaders, it’s no wonder that policy campaigns fall short of the momentum they need to keep up the pressure on decision-makers, change minds and hearts, and achieve solid results.

Community organizations need general support money to cultivate leaders over the long-term. For example, Brian got a call recently from an organizer who received a report and call to action on healthcare reform sent from one of the members of the Virginia Organizing’s Health Care Strategy Committee to its entire mailing list. The member is not an expert or paid staff person, but he once worked as a claims representative for an insurance company. The organizer first met him three years ago at a health care forum, one of many Virginia Organizing did all over the state and not just in “key” Congressional districts. After the forum, the organizer took the time to follow up with a phone call, set up a one-to-one meeting, and invite him to local chapter meetings. The member began to participate in actions. Eventually the organizer invited him to serve on the Statewide Health Care Strategy Committee, where the leader could use his understanding of the insurance industry to explain the issues and encourage participation among thousands of members across the state.

The organizer asked Brian if it would have been possible to spend the time he did to encourage this member to get involved if Virginia Organizing had been solely reliant on national campaign funding. The answer was no. Dependence on federal campaign contracts alone doesn’t allow room to develop the people most directly affected by the issues, move them into long-term local organizing work and relationships, group action on a variety of issues, and eventual leadership roles in the organization.

Deep community organizing works

It’s time to shift the focus of funding and organizing onto leadership development and community organizing that reaches the scale needed to make major change and build powerful community organizations. This approach works, many community organizations in addition to Virginia Organizing have been doing it for years, and it can continue to expand in communities all over the country. Simply repeating the Health Care for America Now strategy over and over again without taking a breath to build and expand the capacity of community-based organizations to develop committed leaders is shortsighted. Here’s an example of how deliberate community organizing and national campaigns fit together.

In 2010, the organizer who covered Virginia Organizing’s work in the northern Shenandoah Valley left to take another position. The board and leaders had been planning to do additional strategic work in Spanish-speaking communities and used this opportunity to hire a bilingual organizer to spend the next several years having one-to- one conversations with Spanish-speaking people, many of whom work in the poultry industry throughout the Valley. All she did for an entire year was one-to-one meetings with people from all across the Valley to find out what issues were important to them. Based on these conversations, a local chapter organized and chose its own issue: to address racial profiling in the Latino community by local law enforcement. The chapter began work to end the local enforcement arrangement the Sheriff had with federal immigration officials.

Because the organizer had met with members from across the community, it was possible to build relationships between African-Americans and Latinos early on through meetings between members from each community. Chapter members learned dozens of skills, including writing letters to the editor, organizing meetings, speaking in public, presenting grassroots education on the issue, doing a power analysis, developing a campaign strategy, and meeting with elected officials. After two years of work, the chapter won the campaign and, just as importantly, had organized an intentionally diverse chapter of directly affected community members who worked to dismantle racism, learn new skills, and alter the existing power relationships in the Valley. Very little of this work was supported by national campaign funding.

As the chapter was working to decide on its next campaign, the national immigration reform issue once again took center stage. Virginia Organizing became the lead organization for the Alliance for Citizenship, leading the organizing in eight of Virginia’s eleven Congressional districts. One of those districts is in the Shenandoah Valley and represented by Congressman Bob Goodlatte, who chairs a key House Committee on immigration issues. The Valley chapters and members were able to turn out four hundred members to an immigration rally in April and followed that up with hundreds of members putting pressure on Representative Goodlatte for months. And yes, there has been a great deal of media coverage. The level of engagement and widespread support for immigration reform in this key district would not have been possible without the years of investment in local organizing and leadership development. Members had learned skills and developed relationships as a group, and could influence decision makers on any issue that might come up.

This is just one example of community organizing providing reach and power to national campaigns. Virginia Organizing was able to do similar work during the HCAN campaign, covering districts and pressuring members of Congress all over the state, all while doing leadership development and building the organization. The organization has done similar work on federal budget issues building on the work it has been doing with members on state budget issues since 2002. Notably, three national organizations helped greatly when Virginia Organizing got started on state budget issues: the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy, and United for a Fair Economy. None of these organizations paid Virginia Organizing to produce deliverables. The organization asked for their help, and they provided research, analysis, training manuals, presentations, and lots of advice to the members of the statewide tax reform committee, the coalition of allies that formed to work on the campaign, and the organizing staff.

None of the national organizations told Virginia Organizing how to run the campaign or which deliverables to produce, but they gave the organization the resources it didn’t have: top notch analyses of tax and spending issues, national and state comparisons of tax systems, analyses of the options for reform, and a curriculum used to complete training sessions with more than 600 people across the state to get ready for the public announcement of the campaign. That support for leadership development continues to pay dividends to national-campaign work on the federal budget today. Similarly, national campaigns help meet their own goals most when they provide solid research, media contacts, coordination, and accurate reports on developments nationally as they unfold.

Virginia Organizing and other community organizations have been able to take the metrics and deliverables from the national campaigns, compare them with their own needs, and tailor them to fit with ongoing work. Virginia Organizing does not assign an organizer to work solely on a national or statewide campaign. Instead, the organizers recruit strategy committees of members from all over Virginia to come together and organize the campaign. This is in addition to the local work those same members do in their chapters every day. The approach has produced a strong grassroots statewide organization and developed leaders all over Virginia. Current national funding priorities need to support the power of community organizing rather than drown it in deliverables.

Building Power for the Long Haul

Community organizing is constantly changing as new energy, groups, and transformational moments arise and as we respond and strategize to address more sophisticated attacks from those in power. Virginia Organizing and a handful of other groups with similar commitments to community organizing are often commended for being highly effective on national campaign or network conference calls. But praising organizations that have figured out how to get all of the deliverables done as well as develop leaders and build real organizations from the ground up is dishonest and counterproductive when the time and work it takes to get there isn’t acknowledged or described. More funders and national campaigns need to respond like the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy, and United for a Fair Economy did to Virginia Organizing by helping groups around the country build infrastructure and follow a long-term strategic approach.

Luck and timing had something to do with Virginia Organizing’s growth and accomplishments over the last nineteen years. But mostly it came from faith in local communities, the board, committees, and staff that people from different races, classes, and communities can work together over time to get done the things they want to get done. Funders like the Catholic Campaign for Human Development, the Needmor Fund, The Unitarian Universalist Veatch Program at Shelter Rock, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation, the Public Welfare Foundation, and the Ford Foundation have funded proposals from Virginia Organizing to them for work the members planned and wanted to do from the ground up. Thousands of individual donors contribute whatever they can afford, from one crumpled dollar bill that arrived in the mail at the office one day to thousands of dollars in a single check. Fundraising events are as continuous as leadership development in the struggle to keep the lights on and, most importantly, doors open. Unlike campaign mobilizations, long-term community organizing produces long-term grassroots financial support.

There are ways to deepen and expand the power of community organizing

Some national groups and networks including the Center for Community Change and the Alliance for a Just Society are already working to bring people together to strategize for the long haul. Some are carving out time and energy to train organizers and leaders, not in how to meet deliverables, but in how to talk about racism, do power analysis in local communities, do one-to-one conversations and house meetings, do research, make plans, take action, and evaluate the work. There are also national groups and networks that are bringing community and statewide groups together to discuss how to build power and work on campaigns in a deeper way than the current contracts for deliverables permit because dependence on contracts distracts from developing leaders and groups of people who can work together. Providing space for people to talk about how to do it will help them decide whether they’d rather try to build organizations that grow in power over time or make misleading, annoying phone calls to people who have better things to do.

A shared reading program is one way Virginia Organizing inspires its staff to keep focused on community organizing and deeper development of the organizer’s craft. Every month the staff works in pairs to choose and read an article or book, and spends at least an hour talking about insights from the reading that influence their work. Sometimes the whole staff reads the same book and spends an hour talking about it. It creates an opportunity to talk more deeply about the meaning of the work. This year the staff read I’ve Got the Light of Freedom by Charles Payne, which chronicles the years of work that preceded the Mississippi Freedom struggle. He writes:

Above all else they stressed a developmental style of politics, one in which the important thing was the development of efficacy in those most affected by a problem. Over the long term, whether a community achieved this or that tactical objective was likely to matter less than whether the people in it came to see themselves as having the right and the capacity to have some say-so in their own lives. Getting people to feel that way requires participatory political and educational activities, in which the people themselves have a part in defining the problems — “Start where the people are” — and solving them.

To achieve profound change that lasts, and policies that improve over time, funders and national campaigns must strengthen the roots of community organizations that make those crucial changes possible. The country needs more groups like Virginia Organizing, funders who understand and support what it takes to build these organizations, and national campaigns that listen and ask what they can do to

help them get stronger from the ground up.

Brian Johns first came to Virginia Organizing as an intern in 2000, and then worked as a community organizer from 2001-2005. He spent two years in Pennsylvania doing community organizing with a labor union, and returned to Virginia Organizing in 2007. He is currently the organizer for far Southwest Virginia, covering from Pulaski to the Kentucky border. He has also served as Organizing Director since 2010, strategizing our Statewide and Federal campaigns and supervising our 10 organizers around the state.

Over a span of thirty years, Ellen Ryan has worked as a community organizer in New England, the South, and the upper Midwest. She served as Lead Organizer for Virginia Organizing Project for six years before moving to Maine in 2006, where she works as a free-lance writer and consults with community organizations.